Table of Contents

In Dust Bunny, Director of Photography Nicole Whitaker brings to life a meticulously crafted visual world to a story that blurs childhood imagination with creeping psychological tension. She offers an insight into the technical side of making the film, including how to make the best of what you have, and the on-the-fly creativity that comes with being on set.

When you got some of the first images or first ideas of the film, how did that influence your work and how you saw [the film]?

Bryan [Fuller] had done some incredible concept drawings [by artist Dan Milligan]. He had done the drawings of Aurora's bedroom, of the bunny, as well as a lot of other different rooms in the house. So it really gave me a good jumping-off point to kind of see where he was going. They were very colourful, they were very animated, so I was able to get a really good sense of what he wanted to do from those drawings, and he showed them to me after our first meeting. So, initially, I just had to come up with a lookbook to get hired, so I kind of figured that out on my own, and was lucky that I hit the nail on the head.

What is your process when the camera is moving around so much, especially when you're working with part practical effects and part CGI? How do you balance that?

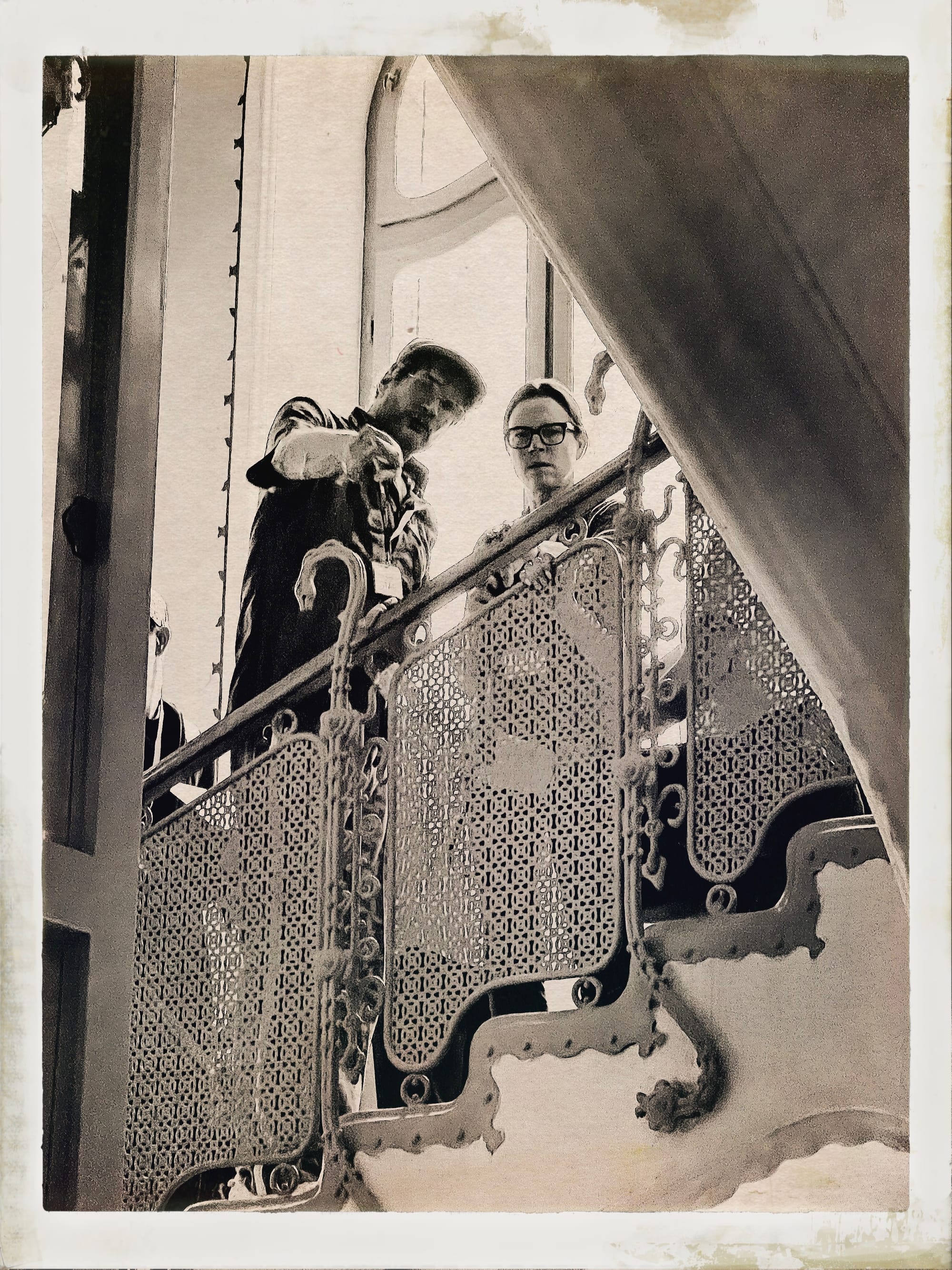

Well, Bryan and I had spent about three months on the ground in Budapest prepping, and part of that process was us basically locking ourselves in our apartment and storyboarding. He did stick figures, it was really fun because he had little bunny teeth for Aurora, and then little cheekbones for Mads [Mikkelsen], and Sigourney [Weaver] had big eyes. So he would basically sit there and draw as we were talking through the script. We spent many, many weeks going through that process. As we were doing that, we would stand up and move around, and he'd kind of show me how he wanted to move the camera. Just because of our budget, we knew we wouldn't have a technocrane every day, but every day he would have a technocrane move. So we had to come up with some pretty unusual ways to move the camera.

The crew was just incredible, and built things from scratch, even sometimes on the day. Bryan would come up with an amazing idea, and he and I would talk through it, and I'd be like, all right, well, we really should have this tool or that tool, and we'd go back and tell the crew what we wanted to do, and they would somehow figure out how to do it manually as opposed to with a remote head or even a three axis head. So it was partially a lot in prep, and then, as we always do, sometimes we figured it out on the fly on the day, if something was inspiring as well. But most of it was pretty well pre-designed. Otherwise, it would have been impossible to do in the schedule.

What were some of these rigs you guys had to come up with?

Normally on a regular-sized show, you'll have a technocrane and either a matrix head or some three-axis [stabilizing] head. We had a Ronin, so we would kind of make due with building things, building trusses, and putting the Ronin on the truss when we didn't have the proper crane and the proper head, and just, you know, gingerly make it work. Sometimes it was a little unstable, and they would stabilize it in post. I should say that we're not used to not having the exact thing that would work for a shot, so that was definitely a challenge, but also really fun. If we did want to do something, and we didn't have what we needed, we could figure it out.

That's kind of like a Frankencrane.

And I have a picture of the Frankencrane. It's an amazing photo!

One of the things I talked about with Bryan was lenses. I noticed about three different kinds. Can you talk a bit about capturing the feelings of this big world and the bits of anxiety?

Our main set of lenses were the ARRI ALFA Anamorphics, and ARRI gave us two sets. We had one set that was very detuned, which you can see especially in the tea house and some of the other shots, and one that was less detuned so that we could have people on either edge of the frame in the 2.40 protection area where you could never put somebody since we shot 3:1. You could never get anybody on the far right or left edges. They wouldn't be in focus. But they were still very specifically tuned. Our AC, Chris Summers, who's incredible, spent weeks with me projecting them. Making charts about exactly how many millimetres someone [could] move to be in focus. Because, unless you're projecting, you're just on a small screen, especially when you're pulling focus. You can't see those nuances. Then we had a few other spherical lenses for visual effect. Those were also ARRI lenses as well, so it was an all ARRI show.

You had to go through that for each and every one of them? Figure out the millimetres?

Yes, we projected them. I mean, they're not huge sets of lenses. So we just projected, we did tests. We projected each one onto a white wall, and Chris mapped them out. He's an incredible focus puller. He would tell me if we needed a little more stop, or we would tell the actors, 'Please don't lean over here if you can.' You know, having a good focus puller when you're shooting anamorphic is invaluable. On top of that, when you're shooting with lenses like this, I never could have done a show like this without someone like him.

There is a lot of French film influence in this one. Everything is very tight, all the colours, the lighting, the music is all working together. Of course, film sets never go the way we expect them to. Things always come up. How was it maintaining such a tight visual aesthetic [if things go wrong]?

Bryan and I obviously started together with the production designer, so we were involved from the very start with designing colours. That was something I could embrace. Then the costume designers came on, and they embraced the colours of the set. So once we were all dialled in together, it was... you know, when you have those kinds of experiences where everyone is on the same page, and we were. So from that point in the production that was the least difficult part because I felt like everybody was on board with the colour scheme. We had influences like Amélie, and other Guillermo Del Toro films, and just films that played a lot with color. Once the sets were done and the paint colours were there they were spot on to what Bryan and I had discussed and what Bryan had designed conceptually before I even started the show. So it was really just about figuring out what was in his head, what he liked, and we were able to find that. We did still play with colors in post, as well in the DI, making things brighter or less saturated in certain situations. But, you know, they're pretty close.

We had a beautiful, beautiful LUT that Dave Hussey, who's Bryan's longtime colorist, and I've worked with a lot as well, [made]. He designed a beautiful LUT for us based on the film references and photographs that we sent him. So we loaded that in as well. That also got us part of the way there from the beginning. Even the stills on set and the dailies were so close to what we ended up with. So we kind of always knew we were in the right ballpark, which was great.

Were there any images or any inspirations that you specifically took when you were shooting? Was there something you were drawing on and trying to see?

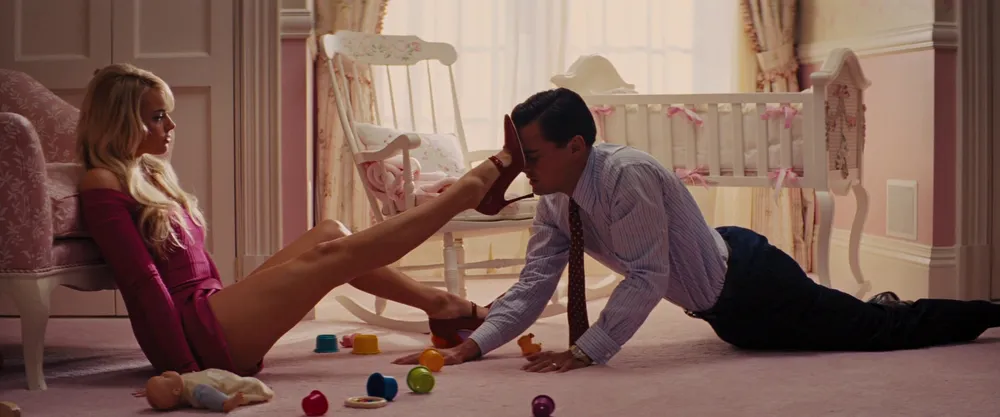

I would say, again, Amélie was probably it in terms of colour; Bruno Delbonnel was a huge influence in that respect. But, you know, we also took from some other [Jean-Pierre] Jeunet and [Marc] Caro films like Delicatessen, and then Pan's Labyrinth, and The City of Lost Children; films that really used colour for contrast, and that was what we played on. It was always in the back of my mind, just like any other type of film like that. Even something more modern like The Green Knight. There's just not a lot of films that do that anymore. I find that there's a trend to be very natural or not do a lot of lighting. So this was really, really fun in that respect, that it was so designed.

I know there was also a lot taken from the '80s and Amblin movies. How did you find your balance, like with what we think of as more artsy and French, and then these kid movies? How was that middle ground?

It's funny because I think of those movies as being artsy. It's just that they're commercially successful. I think Spielberg's films are very artsy, especially if you look back at them. Bryan loves films like The Goonies and things like that, too. I think that it was more for the tone of the film. I wouldn't say that was so much in the cinematography of it, but having fun with the camera was definitely something that we pulled from that as well. Bryan loves to move the camera, and it's really exciting. Even sometimes when you're doing a shot, you're like, how is this ever going to work in the cut? He just knows. He's like, 'It's going to be great, it's going to be this.' It's just also having a captain like that that you can really trust, and just stay on board for the ride is also really, really wonderful. Because I don't know what they're going to do in the edit. I have to also trust my director so much.

It's kind of like trying to channel Amblin themes but with a fully French aesthetic.

Yeah, that's a good point. Again, it was like Amélie with a touch of Fincher. There was sort of this mystique of different filmmakers who are very designed.

And when we're talking about design, going down to the millimetre, I'm sure even the point millimetre, when you were looking at different lenses, how did you find the blocking of the camera?

The sets weren't very big, so there were only so many places we could go. But I really felt like the thing that was so wonderful about it is I still felt like every shot was fresh. There was logistics, and then there was also creative choices as well. If we didn't have the time to pull a wall, we might have to pivot a little bit. But in terms of a shot, how it would work within the story, just because we talked about it so much, it was pretty much always predetermined on the day how we were going to do that. Especially things like the opening shot that was very designed and took a whole day, but it was still in conjunction with our second unit director. So there was a lot of his input. Again, there's so many people that you collaborate on a set with that everybody has some input into how we do things.

At the end of the day, we come in with an idea, and we're like, this is exactly what we want to do. I would say maybe 75% of the time, you end up doing exactly what you want to do, and then the other 25% you have to figure out a way to make it work.

Yeah, so I'm going to ask about that 25%. Was there any moment in the film, or any shot, that you had to do a bit more working around, or a bit more creative problem solving, because it didn't go exactly as the storyboard?

I'll tell you about the hardest shot, and Bryan will probably agree. There's a shot where we pull back through the hall as Sheila [Atim] comes out of the bathroom for the first time, [and] the FBI guys drop everybody onto the floor, and everybody's like 'There's something in the floor, there's something in the floor,' and we had to pull through the hallway. She's the most beautiful woman with the darkest skin and the biggest eyes, and there was nowhere to put the lights. Literally nowhere to put the lights. The hallway was completely taken up by the camera. So we were trying to handhold things to get the lights in, and at one point, I just said that this is going to be one of those shots where we can't pull anything out of this. What you see is what you get.

Because I always like to work the problem, we kept trying different things and it just wasn't working. So that was definitely the hardest shot that took the longest for me to set up. It was partially because we weren't really planning on it, and part of the set that was supposed to pull didn't, so we couldn't get the lights where we needed, and so that was a compromise. But at the end of the day, we did a lot of work on it in post, and I think it's fantastic. I actually think at the end of the day, creatively, it worked better than it would have if she had been lit all the way down because it was more mysterious.

I mean, that's always how it ends up. It always ends up working well.

Nobody would ever know. It's just one of those things as a cinematographer, you like people to have options. I mean, Gordon Willis wouldn't say that, but it's like this day and age, I find if your negative is too thin, it falls apart digitally. So I like to have a bit of space, especially when you're finishing, and you can bring it down. But you can never bring it back up.

When you're working with such a small space, you mentioned the hallway, how were you able to work around the lights and the space [with all the movement]?

It was the same as anything; you can try to keep as much offset as you can. Our spaces were so small we couldn't really put anything on set, and when we did, it was very hard to move around. So that was the biggest challenge. I would have liked the rooms to be bigger. I would have liked to have had more time to pull walls and ceilings and things like that. But you just run out of time, so sometimes you just have to go with it.

It was very, very hot. Bryan and I talked about the set. It was like a spa. That's how we think about it. Now, at the time, it felt like we were stuck in a giant greenhouse. It was really, really hot. There was just no ventilation, so that was tough. But, yeah, what can you do? We always work around it.

A lot of the film takes place from Aurora's point of view. So when you're shooting from a childlike perspective, while you have all of these horror elements happening, how did you design the shots [for both of these genres]?

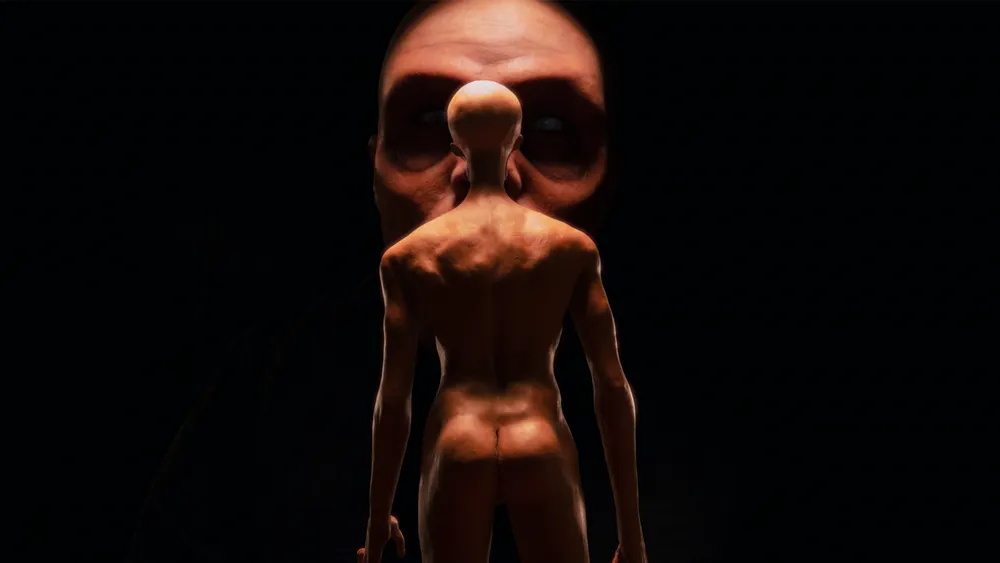

There's so many sorts of traditional horror tropes. Bryan and I watched a lot of films. There's an homage to The Haunting when the door breathes, and there's things that go bump in the night with Aurora and her bedroom, things under the bed. All those wonderful horror tropes that you get to work with. I think it was just really fun to play off of those. We tried to find out our own language as well, because it's a completly original film. It's not like we were copying or remaking anything, and again, it's a monster movie. That's a totally different style as well. Less "bump in the night", more "when do you reveal the monster"? How much of him do you see? That was really the biggest decision: how much are we going to see. Because a lot of it is CGI, that is wonderful because you can decide that later.

You mentioned The Haunting, which I would say is way scarier than something like Ghostbusters. Were there moments where you drew more on kid horror or horror horror?

I have to be honest. I don't know if I was ever really thinking about that. I sort of felt like a lot of that was going to come in the timing of the edit, more than how we shot it. I feel like the shooting was still very traditional. In terms of picking a specific shot and saying, 'This shot is going to be scary,' I think we just picked shots that we felt were appropriate for that part in the story, not necessarily trying to make them scary. The scary, to me, comes from what's going on in your own mind, in terms of what you don't see. If there's too much given away, then you know something's coming. If you shoot things where the premise is that there is something coming around the corner or something coming from underneath the bed, then you're giving away the scare.

Was that part of the planning? Knowing when we are going to show this monster? When are we going to hide it?

I would say no, just because they were able to do that later. We shot a lot of plates and a lot of things they [VFX artists] could move around. A lot of it really happened later in post, 'How long do you wait?' It was in the script, of course, but I think sometimes things change in the edit room. I knew that it was supposed to be at this point, but it could have moved. So I just left it very open so it could happen in different places.

Like, 'We'll shoot it a little longer so they can see how much they want to cut it.'

It was more that, just because visual effects was going to be doing so much work, that we shot a lot of plates that didn't necessarily have tons of camera moves. Then we knew, because they had to build the bunny, that they were going to put the moves in later. If we did a move, we might cut him [the bunny] off. It's hard to know exactly how big things are going to be in the frame. Unless it was something very specific and we had a reference for it, we left it a little bit looser so that our visual effects supervisor could have more wiggle room to play with. The monster is so crazy and big, you don't really want the camera to be moving too much when he's in the frame. Because he's nine feet tall and you kind of want to give him room to move around. Otherwise, the shot has to be so incredibly wide if you're going to do a move that he becomes small as well, so they tended to be more fixed.

Is there anything else you want to share?

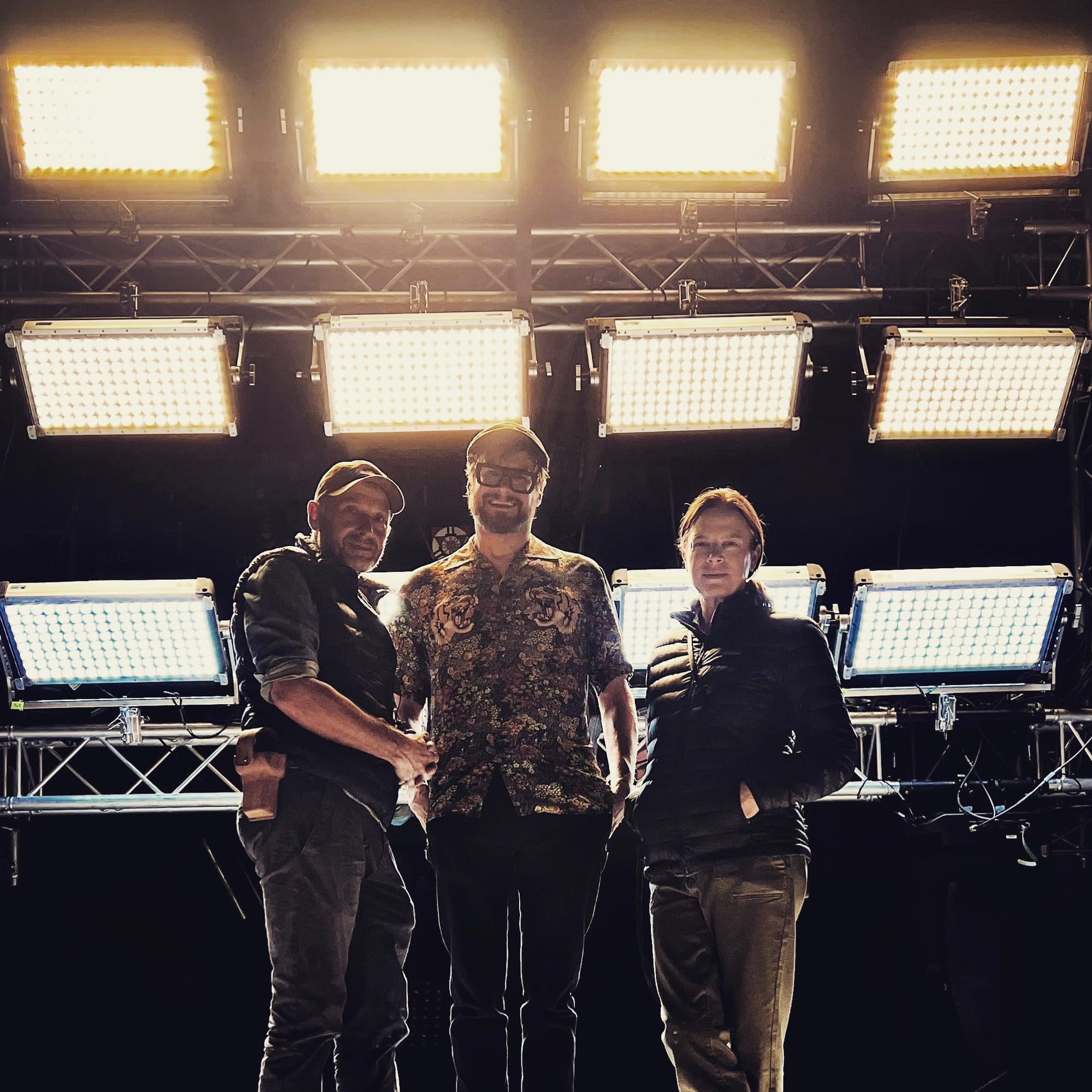

Just that I had such an amazing gaffer, Helmut Prein, who's from Germany, and he had just done John Wick [Chapter 4] with Thunder Road. So when I asked if we could bring him, they were like 'Yes, absolutely.' Then we got to bring in Scott Barnes, our board op from the States, who was incredible. I don't think we could have done this film without either of them. Again, Chris Summers, our AC, [Dániel Farkas], our grip, Dave Hussey, to finish the film, Lisa [Lassek], our editor, Shannon [Leigh Olds], our visual effects editor, and Craig Lyn, our visual effects supervisor. Craig and Bryan and Helmut and I were literally just the four of us in a bubble making this film. Everyone else helped us, but the four of us were in the trenches, just getting through it. It was a lot to bite off. It was really ambitious.

A friend of mine, who was shooting another movie, Death of a Unicorn, had a budget that wasn't that much smaller than ours, and we had four times as many lights as he did. He would come over, and he'd be like, 'How come you have so many lights, and I don't have anything?' I was like, 'I don't know. We asked, and this is what we needed to do it.' We had wonderful people who got us the gear we needed. Like I said, it was really ambitious. So, just really thanking the crew and the locals as well, that really jumped on board and would just roll with the punches. It was a hard shoot, but we still had fun.

Our thanks to Nicole and the Dust Bunny crew. Dust Bunny had its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival and will release theatrically nationwide on December 12th, 2025.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.