Table of Contents

Bryan Fuller is no stranger to pushing boundaries. Best known for his work in television, behind shows such as Hannibal, Pushing Daisies, American Gods, and Star Trek: Discovery, he's bringing his unique storytelling and visual flair to the big screen with his latest project, and his first-ever feature film, Dust Bunny.

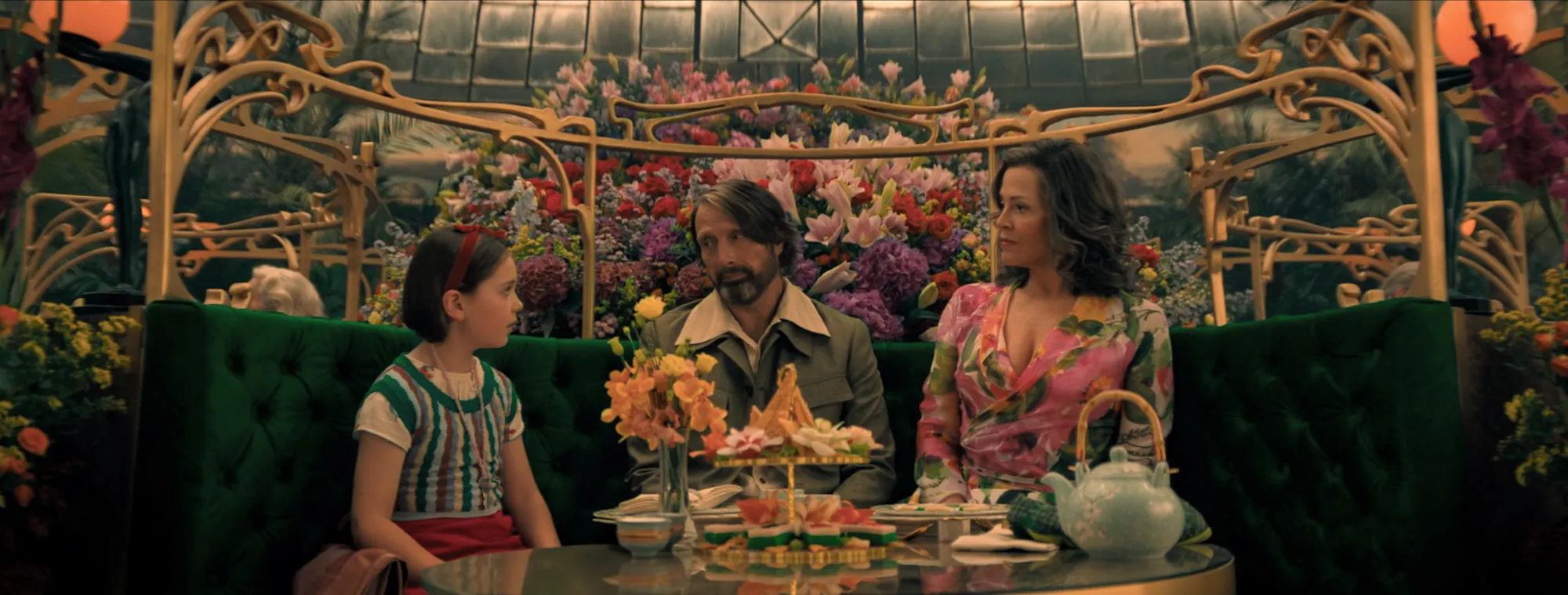

Dust Bunny follows eight-year-old Aurora (Sophie Sloan), who believes that her parents were eaten by the monster under her bed. She elists the help of her hitman neighbour (Mads Mikkelsen) to kill it. Rounded out by Sigourney Weaver and David Dastmalchian, the film is equal parts whimsical and terrifying.

League of Filmmakers sat down with Fuller the day after the premiere at TIFF to talk about staying creative, his inspiration, and the fun part of filmmaking.

When you first got the idea for this film, what was the first image that you saw?

What's been so wonderful about working on this film with the team that we had, its almost easier to say what the first image is when I think of it now because everything has been kind of replaced and enhanced.

The first image that comes to mind is Aurora in Chinatown with a red coat and the bunny mask, which is a creation by Olivier Bériot, our wonderful costume designer, and this kind of superhero silhouette for this younger woman who essentially has been charged with being her own rescuer and has carried that torch as she can, and finds somebody to help carry it with her. I imagine the bunny girl as some kind of icon.

When I was watching the film, I noticed a lot of those '80s kid-centred horror films like Gremlins, Ghostbusters, or Beetlejuice. We don't see a lot of those being made today anymore, like an introductory horror. So what was it about that concept that was really interesting to you?

Well, that was probably my sweet spot of cinematic connection as a child. All those Amblin movies, Gremlins, Poltergeist, Ghostbusters, and the idea of children being in danger. I'm feeling their absence at theatres. They were so much of the staple of summer films growing up in the '80s that I miss them in the marketplace. I miss having that as a choice to get me into theatres.

I love high concepts, storytelling with an emotional centre to it. And Amblin was doing all of those things, and I missed the presence of an Amblin-type of storytelling studio.

When it came to crafting the technical elements of the film, a lot of it is very in sync. The sound lines up with the action and with the editing, and all the costumes and set pieces and decor all match. It gives it a very whimsical feel. So what was it about that technical aspect of the storytelling?

Well I love French cinema, and I love the films of Jean-Pierre Jeunet and [Marc] Caro, his frequent partner. There was something about those films, there was Delicatessen, or City of Lost Children, or Amélie, that have this vibrancy and syncope with all of the styles, you know, an aesthetic, an oral style, and certainly an acting style that has to be cohesive with world building.

So really I would say there's so many directors that when I look at it, I'm like "that's a Barry Sonnenfeld shot," "that's a David Fincher shot," "that's a John Carpenter shot." Those things that we consume as moviegoers, and we process them, digest them, and produce our amalgamated versions of those things, of all of our influences.

Anyone's art is an amalgamation of everything that they've consumed as an artist and processed through their own experience as a human. So I feel that is probably part of the process of evolving from a screenwriter into a filmmaker that gets to take advantage of all the wonderful influences, as well as the amazing directors that I've worked with over the years that have taught me a thing or two.

With keeping everything so cohesive, and as we know, not everything always goes according to plan. How much of it did you have to improvise, and what did you do to keep it in the style?

It was fairly thoroughly storyboarded. We had a couple of sequences that were storyboarded by a wonderful Toronto-based storyboard artist named Dan Milligan. And then I did the rest with stick figures. So with those things, it's often an opportunity, you just start joining shots and when you're like, okay, I have ten setups for today, but I only have time for six. So I have to start combining shots and simplifying things. That's also really fun because it gives you permission to do things artistically but efficiently at the same time, and that's kind of just the adaptation part of the process.

So obviously, you've had a big career in television. Creating something like a film, that is shorter than a full series, what was it like to have to craft something compact?

I mean, it's a different series of challenges. But the television is a marathon, and a movie is a sprint. And there's something about being able to know that you just have to get through these two hours as opposed to eight or twelve or thirteen or twenty-two in television that gives you a sense of presence in the situation that allows you to be adaptable with grace as opposed to television. You have to adapt it, but it's often at a speed that is, you know, fix it in post.

But with movies, particularly with the team that I was working with, what I loved is that there were so many people who had my back, and so many people who were all in the same direction, and so many people who believed in the movie as much as I did. We had our detractors, of course, you do on every set. But that just coagulated the folks that believed in the movie and bound us together, and we all had each other's backs.

Of course, you have a different timeline when you're working on a feature instead of a series. So how did that influence making bolder decisions with the camera work? It was very dynamic.

Well, because it was my first film, and there was so much, so many things that I wanted to do in terms of how the camera moved, I definitely wanted to have a more classic studio style approach. I didn't want to do a lot of handheld. I wanted to keep the camera with a flow that had an elegance to it.

So there was a lot of coordinating the choreography of the camera with the style of the film, and maybe that goes to something you were saying earlier about the cohesiveness. There is a flow to how the camera moves that is in alignment with the emotions the actors are portraying and what's happening on the soundtrack, that if everything is as elegant but odd, then it's all going to come together and feel like it's of a peice.

On that note, there were some different lenses that I noticed used. So again, what was that process in trying to be creative and use as many of these techniques as you can get your hands on?

Well, I was very lucky to work with Nicole Whitaker, who is a fantastic cinematographer and also a wonderful partner for a first-time director, and kind of a big sister in the process. We went to ARRI to look at lenses, and one of the reasons we have such a wide aspect ratio, which I think is the widest aspect ratio in release since [1927], which I think they did a 4:1 screening with three different cameras for a movie, Napoleon. We were testing all of these lenses and looking at, honestly, an emotional reaction as we looked at them. Like, what were we feeling more because it was so much about this little girl's world and whether we were feeling wonder or terror or awe. We wanted to have all of those things enhanced by what kind of lens we had. There was a moment when we were switching lenses, and Nicole took the lens of the camera and took the matte off, and before she put the matte back on, we had this very, very wide aspect ratio.

What that said to us in that moment was isolation and anxiety. And it created a psychological vocabulary for the girl. We want to feel her loneliness and her isolation. So that required to have a lot of space around her, where she's alone and smaller in the frame and not necessarily taking up the whole frame to indicate to the audience that danger could come from any side, and that the isolation also had a slight edge of danger to it. So all that was kind of in the process of going to ARRI.

We had some very specific detuned lenses that they created for us to have opportunities to kind of tunnel vision in scenes. For instance, the tea room scene used a lot of very specific bespoke, detuned lenses that ARRI did for us in Hungary to create a kind of anxiety around Mads [Mikkelsen] in the sequence with these two strong women who are pulling at his purpose in life in completely different directions, and how that needed to create a greater sense of isolation for him.

I know you talked about that emotion, especially because we're following such a young character, and those emotions are going to be heightened in any kind of situation, but especially this kind of situation. It seems like following her perspective and her emotions is a very big part of the film.

A lot of that, I would say, goes to Sophie Sloan's performance, and, you know, she's got those big saucer eyes that just pull you in, and she conveys so much without the dialougue. So I would attribute a lot of that to Sophie.

Because we're following such a young character and you have such a young actor, how do you find working with child actors, especially when they're with such established actors [Mikkelsen and Weaver]?

Well, you know I was very lucky. A good friend of mine, Line Kruse, who was sort of the Danish Jodie Foster in the '80s where she was a young actor. As we were talking, I was telling her about this movie, and she was like, this is what you have to do to protect this child and create a safe space for them that allows them to be a child and still operate in an adult space. And she suggested, basically, "you'd want an acting coach who can be with the child the entire time and be that support presence for them," because it's so challenging being a child. Everything's bigger, you're navigating an adult world, and it's overwhelming, and you don't know what people's personas are going to be on set, how comfortable they are with children.

So she helped create, in [the same] way that we have gotten more familiar with intimacy coordinators on sets – I do think it's just as important for us to have coordinators for young people to create safe spaces and to help them navigate a double world, because they're still children, yet they're professionals. So that helps set the table for us to make sure that Sophie had a great experience. I would hate for her to have done this movie and have been miserable or afraid or unsure. So Line really helped me create a safe space for Sophie.

So when we went onto set, we got to play. And there were simple things that Line was able to communicate to Sophie without the pressure of the director having to say it. Which is, if the director asks you to go again, it's not because you did a bad job, it's because everybody is finding this together, and they won't know until they see it. So they ask you to do different things and try different things as a form of play, and also as a form of finding it and having that not reflect or be about, "oh my gosh, Bryan asked me to do something different." Or "I had prepared something and Bryan wanted me to do it another way." As opposed to taking that in and internalizing it and feeling bad about not living up to a standard, as, you know, kids in general are a bit of people pleasers.

So I think it was really instrumental on the days we just got to play, and we both had the same level of experience. She hadn't led a movie before, and I hadn't directed a movie before. So we were experientially on the same level. So those days are some of my favourite days, because we just got to play and find it together.

Is there anything else that you want to share?

You know, I hope people find it. I hope people enjoy it and sort of want to see something off the beaten track, but also harkens back to high concept, Amblin-era strorytelling. That's what I miss in cinemas, and that's what I'm hoping to bring back.

Our thanks to Bryan and the team. Dust Bunny had its premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival and will release theatrically nationwide on December 12th, 2025.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.