Table of Contents

Lately, new formats have been emerging in filmmaking, from vertical cinematography to ultra-short series episodes. At first, I watched the wave from afar, skeptical but curious. I’ve always loved storytelling that breathes, characters moving through landscapes, space for reflection. But the rise of these new storytelling formats made me wonder: what if I could merge my cinematic sensibilities with this new language of brevity and verticality?

That’s how my two experimental series were born.

The Journey to Origin: Telling a Sci-Fi Epic in 4 Minutes or Less

The first project was a sci-fi short-form series titled Journey to Origin. Each episode runs between two to four minutes. The story follows Sofia, a survivor in a post-apocalyptic world, who encounters Eli a human android and sets out on a journey to find Eli’s creator while being hunted by bounty hunters eager to capture the robot.

The entire series was self-funded, made with indie resources, and filmed mostly outdoors in forests where nature plays a key role in the narrative. We shot it over three months, on weekends, using what we had access to. It was filmmaking in its purest form — experimental and collaborative.

Writing for such a short format was an exercise in precision. I’m used to writing longer formats: half-hour episodes, features, or 10–15-minute short films. So this was a new challenge. I followed a few simple rules that I noticed defined this format: start strong with something that hooks the viewer in the first few seconds, and end with a reveal or a twist that makes them crave the next episode.

But I also stayed true to my voice. I like quiet moments, a character simply walking through a landscape, a pause where emotion takes over dialogue. So Journey to Origin became a blend of both worlds: the urgency of the short format and the pacing of cinema.

Directing the actors was also a fascinating exercise. Sometimes, I encouraged them to take their time in delivering and acting a scene. Other times, I asked them to jump straight into the action or the dialogue, so we could move the story forward faster. It forced all of us to adapt, to distill performance, rhythm, and storytelling down to their essence.

The Vertical Western: Experimenting with Aspect Ratios

My second experiment was with vertical filmmaking, something I used to absolutely despise. To me, the vertical format wasn’t cinema; it was “content.” And I didn’t care for content.

But then, I remembered how film history has always been a story of changing aspect ratios from the early 1:1 silent films to the 4:3 television era, from widescreen CinemaScope to experimental formats used by directors like Xavier Dolan or Robert Eggers. Even I Am Not Madame Bovary had circular framing. So why not experiment with verticality myself?

Almost no one has fully explored this format to its full potential yet. Damien Chazelle directed a commercial for Apple shot vertically and that opened my eyes to the creative potential of this new frame. So, I decided to test it with one of my favorite genres: the Western.

With my cinematographer Daniel, we talked about reframing the codes of the genre. Westerns are usually defined by their vast horizontal landscapes: endless skies and sweeping plains. We wanted to see what would happen if we flipped that. We gave the image height instead of width: the hills became taller, the sky more infinite, and our characters more imposing within the frame.

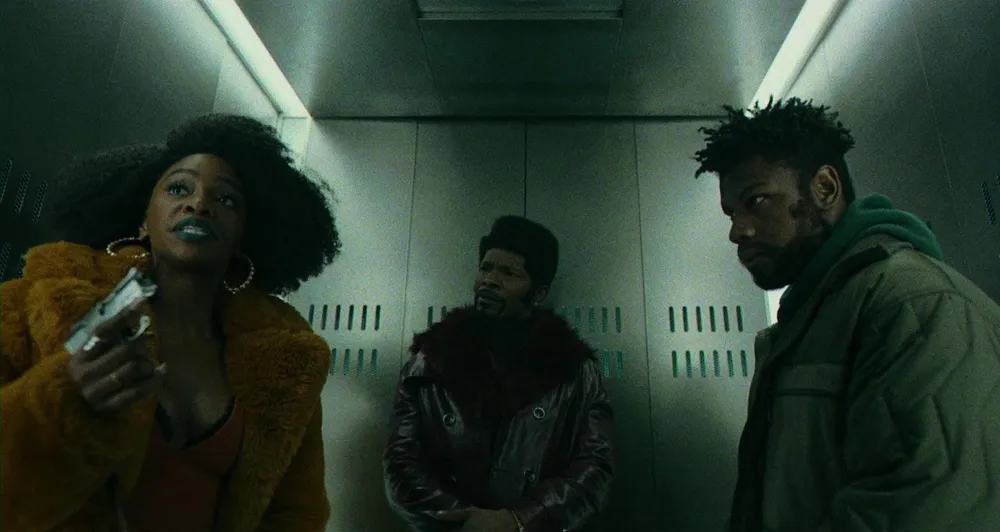

We also leaned into the grammar of Sergio Leone’s cinema: close-ups, tension, and silence, but adapted it to the vertical frame. I wanted to play with the codes of the Western through cinematography, adding my own twist with the vertical format, but I also wanted to add a twist to the type of story I would tell. While I still included some codes of the Western genre such as a lonely cowboy, a gang of outlaws and gun fights, the lead character of this Western is a complete new profile to this genre. Our story follows Ryūji, a Black samurai who flees Japan after its downfall to start a new life in the American West. When his katana is stolen by outlaws, he’s forced to learn how to survive in a land where honor means less than how fast you can shoot.

Each episode was under three minutes. But instead of always ending every chapter with a twist, we chose to build tension gradually: the kind of suspense that stretches across the whole series and explodes in the final showdown.

Freedom Through Experimentation

Shooting these two projects back to back– one short-form, one vertical– was transformative. It pushed me beyond my comfort zone and helped me rediscover why I fell in love with filmmaking in the first place.

For years, I clung to traditional storytelling rules, to the sacred structure of three acts and 16:9 framing. But experimenting with new formats felt liberating. It reminded me that cinema is not defined by its shape or length, it’s defined by emotion, by the power of a story to move you.

Vertical filmmaking is still a new and underexplored field, and short series are an exciting storytelling challenge. But ultimately, what matters most is not how you tell your story, it’s how good the story itself is. The format is just another brush to paint with.

So if you’ve been stuck following the rules or afraid to try something new, take this as your sign. Experiment. Fail. Discover. Maybe the thing you’ve been dismissing as “not real cinema” is exactly where your next artistic breakthrough is waiting.

Cinema has always evolved and as filmmakers, we should too.

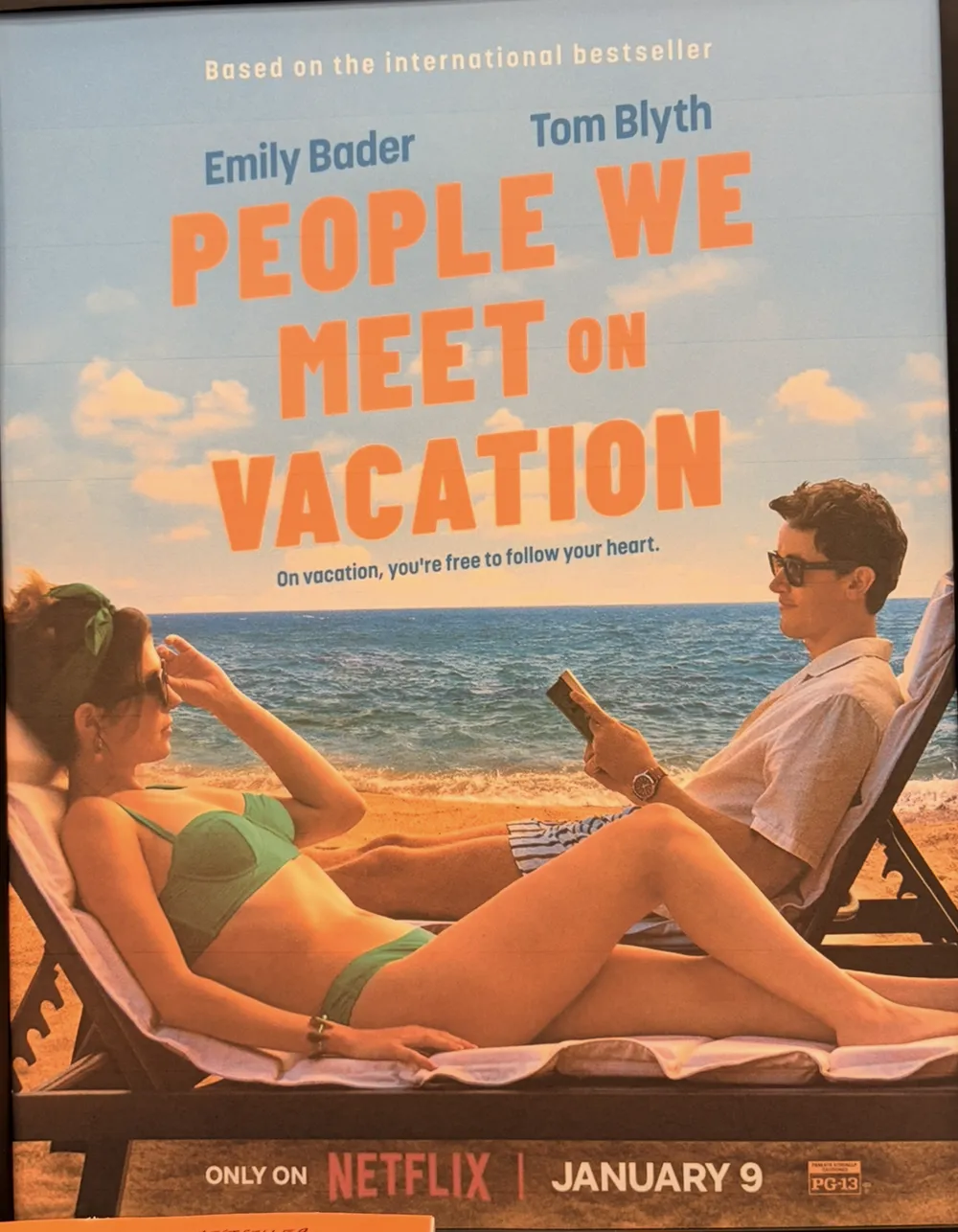

These experimentations eventually inspired me to take things even further, to not only create stories in new formats but to build a home for them. That’s how I co-founded Pocket Cinema, the first genre-driven vertical (and horizontal) short series app, set to launch at the end of 2025. Both Journey to Origin and our vertical Western, Blade & Bullets, will be part of the first slate of releases on the platform. If you’d like to be among the first to watch them when they premiere, you can sign up for our newsletter at pocketcinema.info/app.