Table of Contents

“Their punishment, talking to me, was apparently more fun than the actual work....”

I finally had a story worth telling. I had returned from research in the field, during which I had gotten to know a couple of Los Angeles hookers, Cheryl and Debbie. I happened to like both of them a great deal, a sentiment that all of my male colleagues found impossible to fathom. Thus, the intriguing twist in the story I wanted to tell was less directly about the prostitutes’ profession and more about the deeply held beliefs and prejudices others harbored toward them.

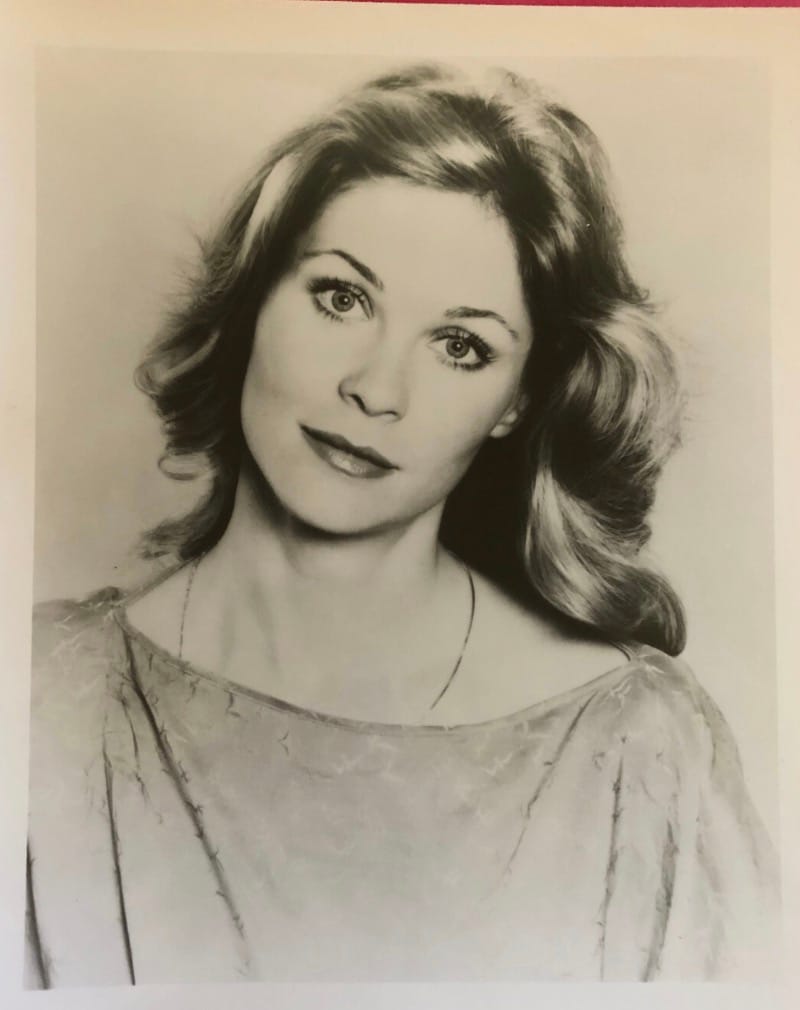

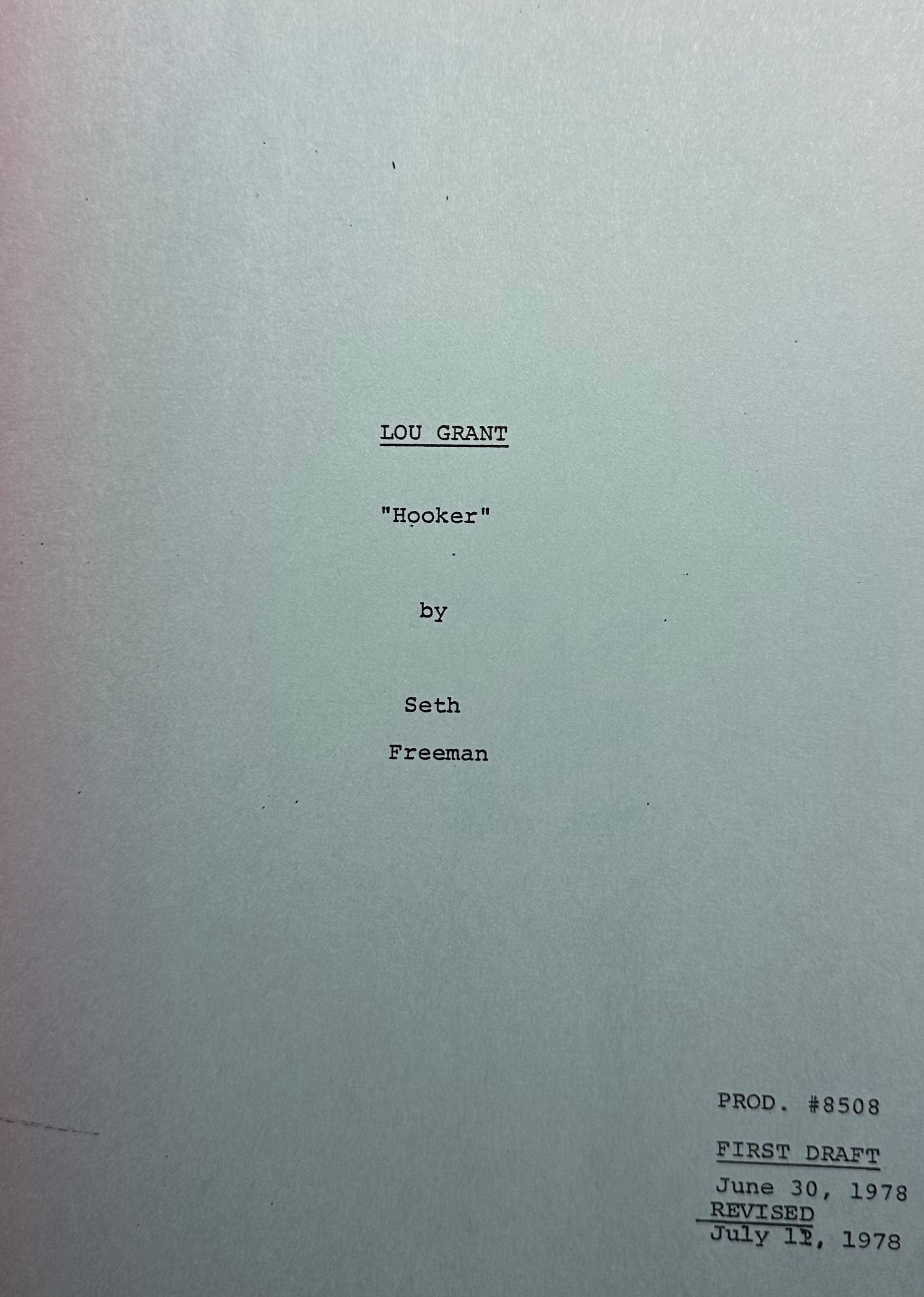

In the episode I ended up writing, called “Hooker,” starring Dee Wallace (who soon became familiar to movie goers as the mom in E.T), a reporter meets a young woman about her own age while covering a police beat story of a massage parlor bust. The young woman who works at the massage parlor has aspirations to do more with her life. She is bright, personable, funny, and attractive. When the reporter, Billie Newman (Linda Kelsey), returns to the news room and tells Lou how much she likes the hooker she met, Lou reacts with disbelief and disdain. “Think about what you’re saying,” he tells her. “She’s a prostitute.”

Embed from Getty ImagesIn a later scene, Lou finds Billie having lunch with a friend in the nearby reporters’ hangout. He joins the two young women for a time, and tells Billie later what a lovely person her friend is. “A pal from college?” he asks her. The friend was, of course, the hooker Billie had met earlier.

My new hooker friends, Cheryl and Debbie were assigned, as part of the community service required as their punishment for hooking, to talk to me and answer my questions. They took seriously my request to be educated about their profession. They insisted that I couldn’t get a real feel for what it was all about without spending a shift in the actual massage parlor where they worked. Thus, one cool early fall evening, I found myself walking up the steps to the porch of the pale blue clapboard bungalow in Santa Monica in which Cheryl and Debbie made a living.

There were two other young women working there that night as well. Their names were Brandy and Amber. Of course. Prostitutes never use their real names. Work names are employed for safety reasons, but I also think it enables the women to separate in their minds what they are doing to make a living, from who they feel they truly are.

Cheryl and Debbie parked me in the kitchen of what was once somebody’s home. Almost immediately, I overheard a fractious kerfuffle between the women and the owner of the massage parlor. I could also have listened in on some of the verbal exchanges in the front room between the women and potential clients, but I wasn’t comfortable eavesdropping, so I just hung out and waited for them to come in and chat if they felt like it. They did. Their punishment, talking to me, was apparently more fun than the actual work. Some of that night’s customers might have gotten a little less time than they paid for.

By no means were all the prostitutes I met while doing research for this episode as bright and appealing as the two I’d happened to come across in that first meeting. Cheryl and Debbie were special. If my research hadn’t led me to them, I might not have found my way into the story: the cognitive dissonance in people’s views of women who work in the world’s oldest profession. With that story, the episode we ultimately filmed worked out well and turned out to be one of the series’ most highly regarded.

This story – the real life story – has a coda, a couple of them actually, but the first was a dismal turn of events which I never could have seen coming. I had continued to hang out with both Cheryl and Debbie, but eventually we lost touch. Then I happened to bump into Debbie, who was working at a florist shop in Santa Monica. She told me that Cheryl had found some success as a porn movie actress and also that she'd had a baby. Some years after that, I received one of those mass distribution postcards in the mail, the kind which contain the sort of messages which we used to see on milk cartons, flyers for lost or abducted children. Under the heading “Have you seen me?” was the picture of a little girl with more than a passing resemblance to Cheryl. There was also a photograph of Cheryl.

The text said that the adult shown on the card was believed to have kidnapped the child. There was a reward for information leading to her apprehension.

The second coda occurred much more recently, about three years ago, when, shortly before Christmas, I received a letter from an East Coast state, from Cheryl. There was a phone number, which I called, and we had a good catch up conversation. She had in fact kidnapped her own child in a custody battle with the father, and, as it turned out, she had been caught by authorities and had her daughter taken away from her. But she continued the legal fight to be reunited with her daughter and eventually the courts decided in her favor. She was able to get her daughter back and to raise her. Cheryl was a good mom. Her daughter went to college and then to graduate school, earning a Master’s degree and becoming a therapist. Cheryl now works in a straight job herself. She is happy. She and her daughter have an excellent relationship.

[To be continued….]