Table of Contents

Throughout the past decade, South Korean pop culture has had an immeasurable influence on the American media zeitgeist. Beginning with the worldwide debut of K-pop group BTS in 2015, and reaching an unprecedented peak of popularity with the release of Netflix's Squid Game in 2021, the unique aesthetics and cultural sensibilities of South Korean entertainment have permeated virtually every corner of contemporary American consciousness.

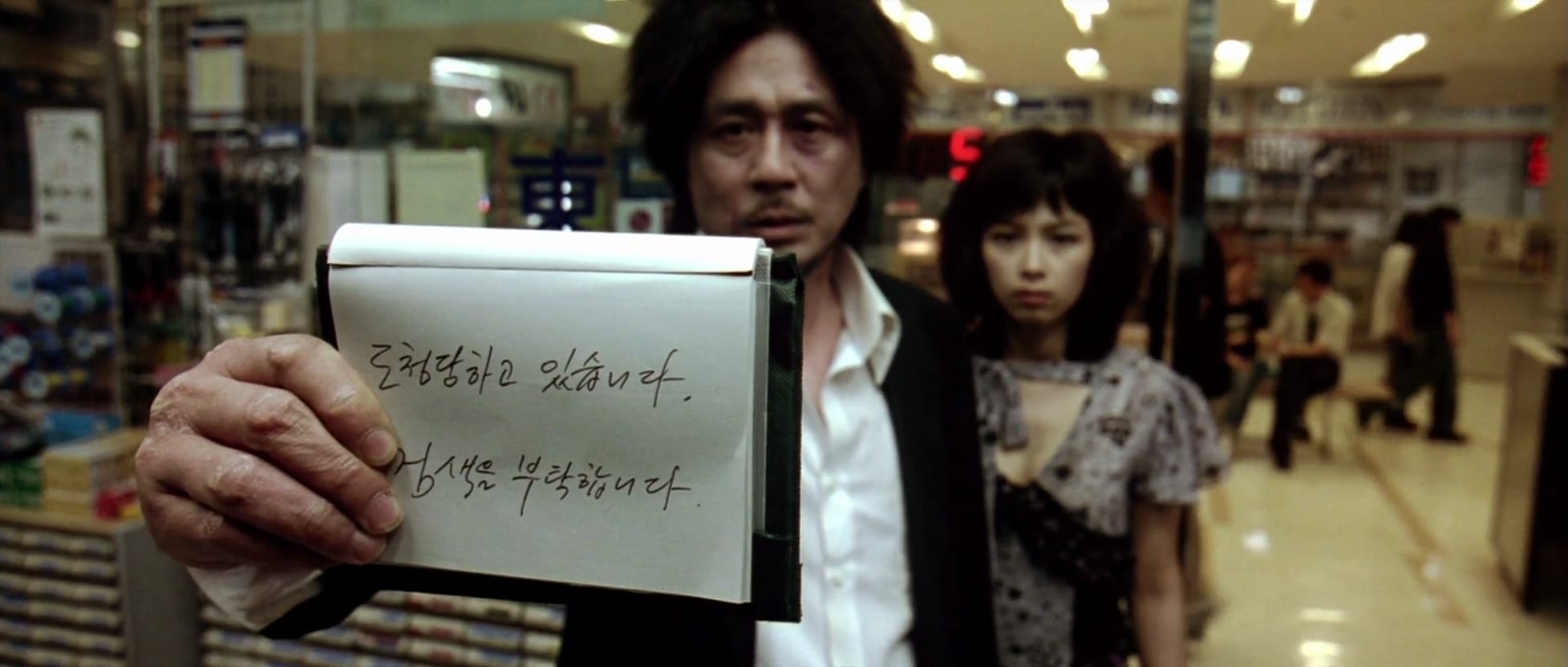

The most recent addition to South Korea's ever-growing repertoire of influence is their film industry. Though genre pictures like Train to Busan and Oldboy garnered significant praise within the most diehard film circles, South Korean cinema was largely underestimated in the United States until Parasite's historic sweep at the 2020 Academy Awards. Bong Joon-ho's darkly comedic thriller found massive success at both the box office and awards circuit, opening the door for other international films to secure large-scale distribution in American theaters. A handful of notable non-English directors have taken advantage of this newfound mode of theatrical exhibition, including Hirokazu Koreeda, Jafar Panahi, Céline Sciamma, and more. However, no filmmaker has capitalized on this unique opportunity more confidently than South Korea's very own Park Chan-wook.

No Other Choice Succeeds...

While 2025 saw the release of several high-profile foreign films in American theaters, none seemed to delight critics and audiences quite as much as Park Chan-wook's No Other Choice. The film follows Man-su (Lee Byung-hun), a desperate father who hatches a sinister plan in order to secure a new job. While much of the film's appeal can be attributed to its star-studded cast and impressive arsenal of formalist tricks, I believe that the greatest strength of No Other Choice lies in the thematic strategies of its screenplay.

Despite being adapted from Donald E. Westlake's 1997 novel The Ax, nearly every scene within No Other Choice is steeped in the cultural specificity of South Korean life. During the first act, Man-su repeatedly juxtaposes the American metaphor for losing one's job ("to be axed") with its Korean counterpart ("off with your head"). This aggressive contrast of figurative language is key in understanding the cross-cultural appeal of the film's narrative, as director Park leans into the unique perspective of South Korean culture in order to make a larger statement on the oppressive nature of living under capitalism. These ideas are further supported by the film's empathetic positioning of the murderous Man-su as its protagonist – a decidedly untraditional move in the realm of Hollywood blockbusters, but not totally uncommon in the canon of East Asian genre films. While it's easy to condemn Man-su's violent actions from afar, Park's stellar screenplay ensures that audiences are drawn fully into his frustrations.

Put bluntly, the ingenious implementation of South Korean culture and ideology in No Other Choice does not ostracize Western audiences. Instead, the exact opposite occurs as the film's themes achieve a greater level of cross-cultural resonance due to the unique details that director Park includes in its screenplay.

Where Mickey 17 Fails

Released in February of the previous year, Mickey 17 served as the long-awaited follow-up to Bong Joon-ho's Parasite. The film follows Mickey Barnes (Robert Pattinson) during his time with the Niflheim space colony as an "Expendable" – a disposable employee that is brought back to life via cloning whenever they are killed.

Adapted from an English-language novel and boasting a budget of over one hundred million dollars (more than twice that of director Bong's second most expensive film, 2017's Okja), the existence of Mickey 17 feels strongly disconnected from the rest of director Bong's legendary filmography. This complaint is most supported by the film's various attempts at thematic nuance, which often feel like half-baked retreads of social criticisms that director Bong had explored more effectively in his previous works. To illustrate this point, we need only consider the overt class critique at the center of Mickey 17, and compare its effectiveness to similar ideas found in Parasite.

Within Mickey 17, the titular character's role as an expendable employee works as the film's central metaphor. This concept is interesting in theory, functioning as an absurd sci-fi take on the way that low-level employees are treated by corporations. However, the metaphor quickly begins to falter when combined with the film's largely unserious tone and unfocused vision. The result of these compounding issues is a film that has more in common with the pulpy sci-fi comics of sixties America than with a serious work from a world-renowned auteur.

In contrast, Parasite is much more explicit and effective in its ideology. While the gap in quality between Mickey 17 and director Bong's previous film can be partially attributed to the greater creative control allowed by South Korean productions, it does not fully account for the difference. Bong Joon-ho's screenplay for Parasite does not just introduce interesting metaphors, but also engages with them to their fullest extent. From the appearance of a distinctly Korean "scholar's rock" to the thematically relevant inclusion of Native American imagery within the film's bloody finale, Parasite stands as a work with a great deal to say and a unique way to say it.

Looking Ahead

Through its commercial success and trio of Golden Globe nominations, No Other Choice has demonstrated that American audiences are still interested in the culturally rich work of South Korean auteurs. In contrast, the thematic failures of Mickey 17 were well reflected in its critical and commercial reception, ultimately proving to be a massive misstep for Bong Joon-ho. However, a single mediocre film does little to diminish his standing as one of the greatest writer-directors working today. There is a relevant Korean proverb – "even monkeys sometimes fall from the trees" – which metaphorically suggests that even experts will occasionally make mistakes. With the release of Mickey 17, director Bong may have fallen from the tree of global cinema stardom. However, it's only a matter of time before he makes his way back to the top (possibly even surpassing director Park in the process).